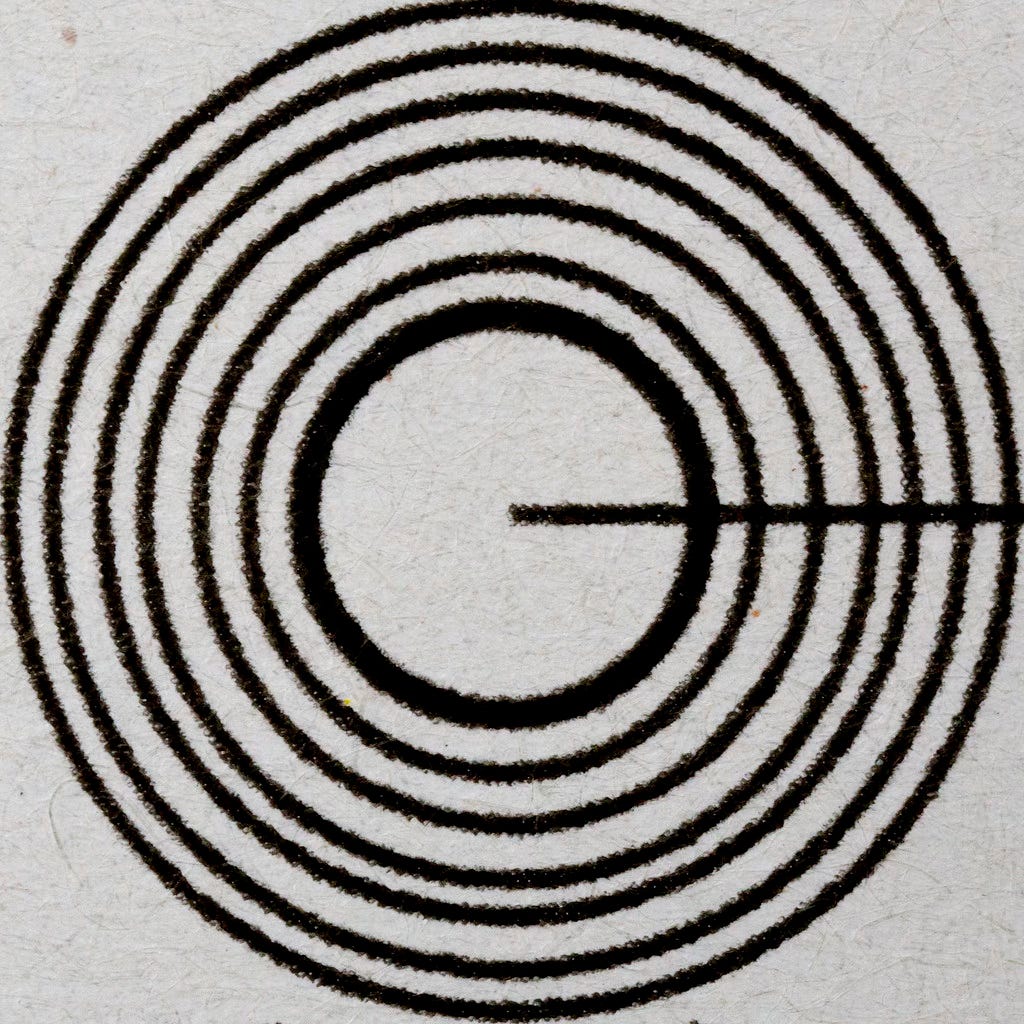

Finding your focus.

Issues of alignment

At this time of year my students are thinking about their first assignments. Additionally, they are asked to think about how their academic interests might translate into a research project for a dissertation- the first step towards writing a dissertation proposal. This post is a description of a lecture I gave recently to help students find their focus (Mason, 2002) by thinking about ‘a context’, ‘an area of study’ and ‘a problem’ that they may want to investigate and write about. I ask students to reflect on their lectures and ask themselves, ‘what am I interested in’?

The main difficulty for students, I would suggest, is finding an ‘area of study’ to focus on. It is not easy to separate something out because academic topics in social sciences are ‘messy’ and overlapping. Nonetheless, postgraduate students must show that they can identify an area of education and a problem or social concern within that area. In assessment terms it is a demonstration of systematic knowledge through reading and note-making. This involves asking reflective questions such as: why is this like this or how did this come to be? This is part of a process of making sense of the messy social world we live in. With regard to ideas of messiness it might be useful to read my previous post on ‘memory, narrative and positonality’ where I refer to the ‘memory maker scene’ in Bladerunner 2049. In this vein I suggest that students start with themselves and reflect on their positionality- as a series of un-curated and messy memories. In my recent lecture I asked students to describe a memory or feeling related to teaching and/or learning to start the process of curating memories and experiences. The is the first step on the path to identifying an interest and describing a personal narrative. It is an important step because positionality is fluid and must be aligned and re-aligned if it is to be useful in an assessment task.

Some aspects of positionality are culturally ascribed or generally regarded as being fixed, for example, gender, race, skin-color, nationality. Others, such as political views, personal life-history, and experiences, are more fluid, subjective, and contextual. (Chiseri-Strater (1996) in Holmes 2020 p2).

In this sense positionality can be defined as essential personal context for the purpose of writing an academic paper. It can also be defined as personal research context or research position for a dissertation study. In other words a dissertation is a study where the researcher must align their positionality with their methods of data collection and dat analysis. Moreover, if positionality is a description of what you know, research position is a description of the alignment between what you know and what you want to know. Additonally, positionality must be revisited throughout a paper as reflections on self- reflexive writing.

In summary, I believe that ‘finding your focus’ begins with a narrative for writing a title and research question. However, this is an iterative process where re-draughting is an ongoing engagement with academic literature. In other words, as the student comes to know more about their chosen area of study, they also become more familiar with the concepts they read about and want to use as key terms in their ‘title’. Their goal is to align a context, area of study and problem in a title and main research question. I am grateful to Ning Rong, a former student of mine for kindly sharing her dissertation title and research questions here. In this example Ning is a Chinese teacher who worked in Hong Kong. she has reflected on her experience of teaching Chinese to English speakers from the financial sector in Hong Kong. Her context is teaching Chinese as second language in China (to English speakers). Her area of study is professional identity (and teacher voice) and the problem she has identified is a lack of professional identity in Private Language Institutions. This alignment is made clear in the introduction to her dissertation. Her title and research questions:

Negotiating the Professional Identities of Part-time Chinese Second Language Teachers in Private Language Institutions on Mainland China.

How do part-time CSL teachers perceive their professional identities?

What tensions do CSL teachers face in their teaching practice?

How do CSL teachers negotiate their professional identities?

References.

Holmes, A. (2020) Researcher Positionality - A Consideration of Its Influence and Place in Qualitative Research - A New Researcher Guide. In: International Journal of Education.

Mason, J. (2002) Chapter 1, Finding a focus and knowing where you stand. In: Qualitative Researching 2nd Ed. London: Sage.

You are too kind. But yes that's my goal :-)

A good teacher knows how to guide students to find their own answers. Thank you Martin!